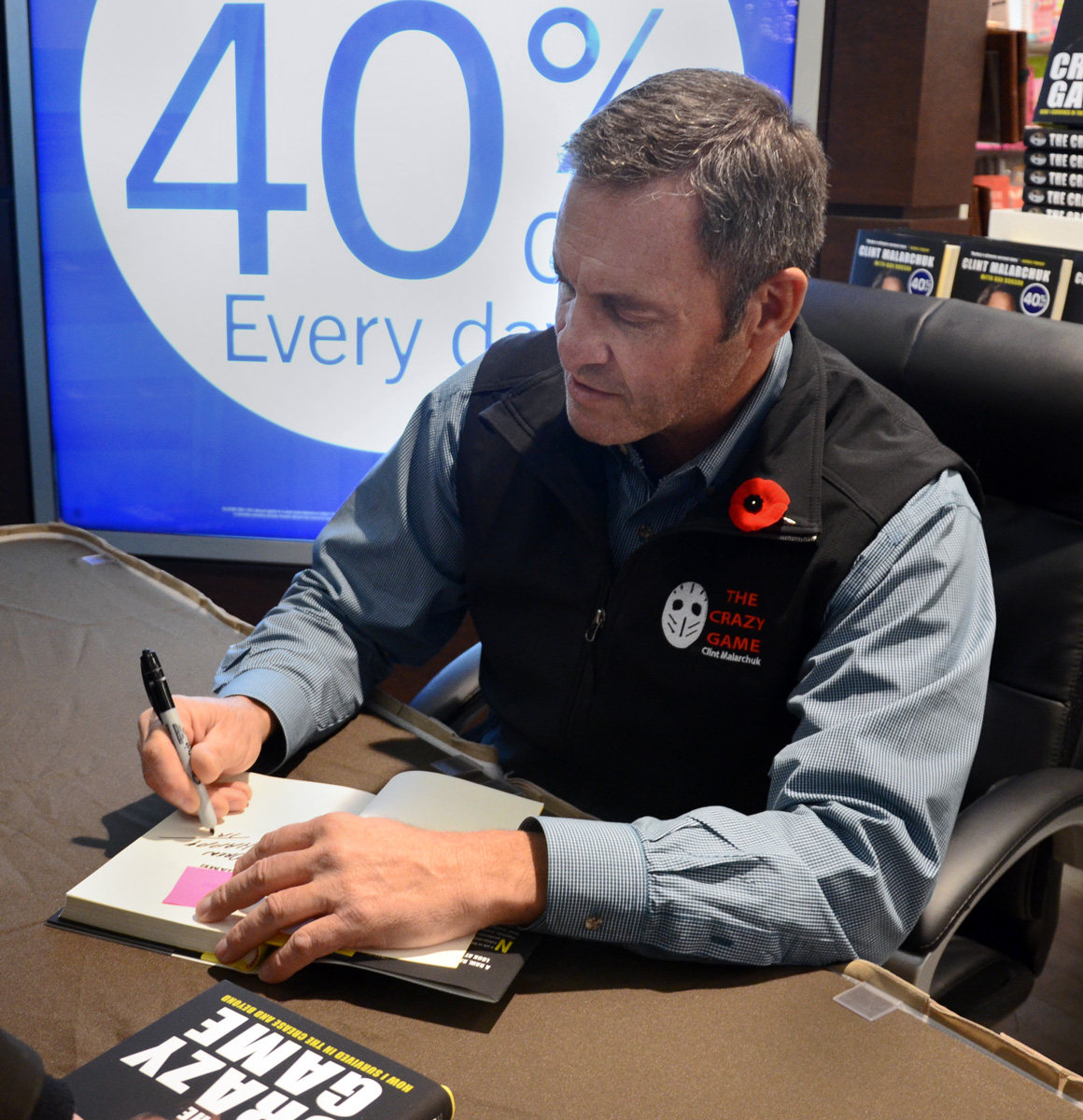

Clint at his book signing in Grande Prairie. Photo by Stan Neufeld

Early Childhood and Grande Prairie Roots

Clint’s story has been told many times: in his book, “The Crazy Game”, in interviews that have been recorded and in numerous speaking engagements and workshops throughout Canada and the United States. An attempt is made here to focus on his connection to Grande Prairie and emphasize the role of a number of especially important relationships in his life. Clint’s journey began on May 1st, 1961 in Grande Prairie, Alberta and if his wishes are followed, his journey will end - where it started - with the sprinkling of his ashes in his hometown. In an interview with Stan Neufeld Clint stated, “I’m a native of Grande Prairie. That’s one thing I’ve always been proud of. I have family there, I was born there, and it’s also my hockey roots.” At age three, bob skates were strapped to his feet and on a slough on the outskirts of town is where Clint’s on ice adventures began. Hockey was in his genes and even at age three one might have known that hockey would play an important role in his future. Clint’s older sister Terry helped teach him to skate.Clint’s grandfather, Leonard Henning, was a competitive speed skater and became a prominent figure in the development of young hockey players following his transfer to Grande Prairie in 1928 when GP Hockey Legend Max Henning, Clint’s Uncle and surrogate father, was four years old. Equipment may have been second hand, but Leonard made sure that his son, Max, had skates, sticks and hockey gear. Along with Bert Bessent they helped organize games and provided transportation enabling the boys to compete against teams from nearby communities. Clint’s Uncle Max was a tough and talented hockey player. For many years he entertained local hockey fans playing defense for the Red Devils, and for teams such as the Key Club, a team that he organized for returning veterans after WW11 and later for the Grande Prairie Athletics. He went on to become a leader in Grande Prairie hockey circles making sure that there was ice and an administrative framework for the next generation of young people to play the game. That generation included Max’s son Cam who also played with the Athletics. That’s a remarkable tradition - three generations of hockey players and volunteers each generation serving as role models for the next. On the other side of Clint’s gene pool was Clint’s father, Mike Malarchuk who also learned to skate and play hockey on ponds in Grande Prairie and is remembered in his hometown as a skilled and prominent goal tender for senior teams in the South Peace Hockey League. With Mike in the net Grande Prairie won several championships playing against talent-laden teams in the South Peace Wheat Belt Hockey League: teams such as the Hythe Mustangs and the Dawson Creek Canucks.

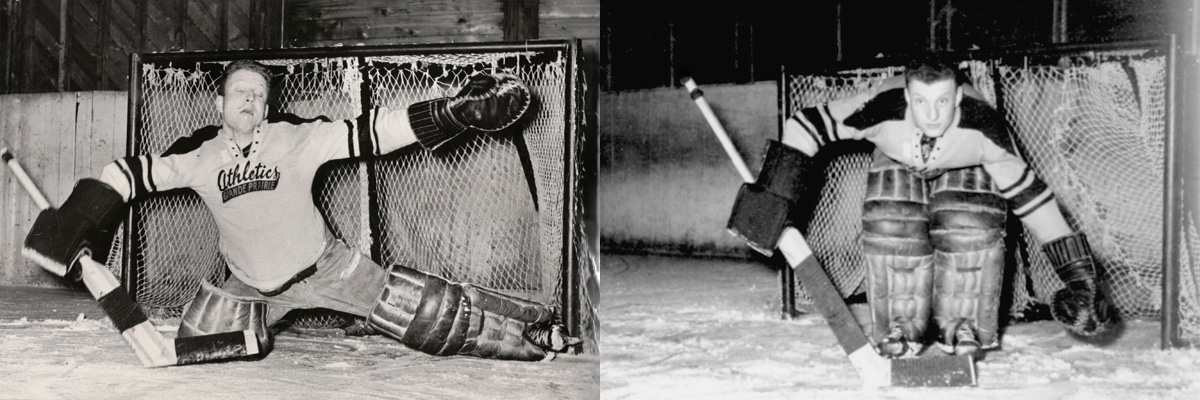

Mike Malarchuk - Goaltender for Grande Prairie Athletics in 1955-56. Stan Neufeld photo collection

Garth, Terry and Clint Malarchuk. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

Clint Malarchuk minor mite hockey team - note the sweater. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

With coaching from his older brother Garth, Clint was beginning to shine as the great goal tender he was destined to become. “That was a big deal and even more of a big deal is that I had a lot of relatives in Grande Prairie who came to watch. I was playing hockey and just started to get good at playing goal. My Aunt Marie and Uncle Max Henning came to see me. Aunt Marie gave me a good luck charm which I still have. “ (Malarchuk interview with Grande Prairie Herald Tribune editor-in-chief, Fred Rinne). Hockey Legend Marv Bird was coaching the bantams from Grande Prairie and recalls being puzzled upon seeing the name Clint Henning on the Edmonton score sheet. For a short period Clint changed his name from Malarchuk to Henning, his mother’s family name reflecting Clint’s alienation from his dysfunctional Dad.

Clint (Henning) Malarchuk - front row second from left. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

The Malarchuk’s move to Edmonton started out well enough but the family drifted into a troubled period as Mike spiraled downward into alcohol addiction, a disease that would eventually destroy him. In his book, Clint includes a chapter about his Dad. Hockey was Mike’s life. He was very much involved in coaching and in other ways supporting the hockey programs in which both Garth and Clint participated. He was popular in the community and was Clint’s hero before he sank into dysfunctional addiction and became a threat and liability rather than an asset to family life. Clint’s name change to Henning proved to be impractical as he was the only one of the children to do so and furthermore both Clint and Garth had established names for themselves in hockey as Malarchuks. By the time Clint was playing AA hockey in Edmonton for the Canadian Athletic club he was playing as a Malarchuk.

Mike’s out-of-control drinking resulted in a number of predictable negative consequences for the family including poverty, emotional insecurity and embarrassment. Clint was fortunate to have caring siblings, Terry and Garth who were seven and eight years older. As mentioned earlier, Terry helped teach Clint to skate and in other ways looked out for him. Following in his father’s footsteps, Garth was a goal tender and shared his knowledge with his kid brother. Clint’s all time favourite Christmas present is still a goal-tender’s catcher that Clint received from “Santa” - Garth - when he was away from home playing junior hockey. Although Garth did not play in the NHL, the Washington Capitals drafted him: a team that is now included on Clint’s resume. Garth is currently a scout for the Toronto Maple Leafs. “Garth is pretty much a hockey nut like I am. He played, he was drafted, he had a lot of skill and a lot of talent. Being older than me he was my idol. He was a goalie and that’s what got me into the position - watching him as a younger brother. I looked up to him, my big brother; I always tried to make him proud of me.” With Garth leaving home to play hockey and Terry marrying early, Clint and his mother were left to fend for themselves in very uncertain circumstances. A powerful bond developed between them as together they confronted the challenges of a broken family. Today Clint claims his mother, Jean, is the strongest person he knows.

Clint and his catcher mitt. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

Garth, Jean and Clint. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

Bobby Orr, Clint and Mike Walton at the hockey camp. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

Early prototype from the Malarchuk family mask. Photo courtesy of the Malarchuk family

It was in Grande Prairie where Clint’s second love developed – hockey is his first love, horses his second. His uncle owned an acreage on the outskirts of town where he kept horses. A friend of the Henning family, Lloyd Finch owned a genuine ranch southwest of town, one mile west on the correction line and a mile south of Flying Shot Lake where they kept horses, cattle, sheep, hogs and chickens. Bob Finch, Lloyd’s son, shared some of his memories of Clint as a youngster with Neufeld: “We were quite a bit older than him but I recall Clint was a determined young fella. Most vivid memory was slopping the hogs with two five-gallon pails of skim milk. We had to pack this stuff at least 50 yards. As a little guy there was no say quit in him. He would pack those pails and I’d tease the little bugger that he couldn’t do it. He’d bow his neck and haul those pails over to those hogs regardless. When I heard that he’d gone to play hockey I knew he would do good because he had a lot of stay in him. We would break a critter and in the process, well, you know how older guys tease young guys. We told him to do stuff and he would naturally get a little excited. There certainly would have been a case where a bull charged at him and chased him for 10-15 yards. In reality, we probably had a saddle horse with the bull tied on but he wouldn’t have known that so he’d run half way across the field to get away from the bull. When he told that story in the book there was truth to it. In his eyes, it was pretty big for a little kid. At that time, he was just another kid hanging around the farm. As he grew up it was a great treat to have him as part of our family. Also we were good for him too because of his background. Our family was pretty grounded and he was treated just like one of the boys. I like to think we treated Clint just like a younger brother.”`

All around Finch’s six hundred acres was wildlife – bears, wolves and coyotes - that were a threat to the cattle. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn had the Mississippi River as their playground and a raft to explore it. Clint and Tim had countless square miles of pasture, fields, boreal forest, rivers, sloughs with horses to ride and explore the rangeland. It was an idyllic context to help a city boy find moorings. It was on the Finch Ranch that Clint acquired his identity as a cowboy learning to ride, rope and shoot. In the tradition of cowboy culture and the Wild West, Clint recalls how he learned to use a gun. The ability to handle a gun came in handy on one occasion when he was fourteen. It was late afternoon - Clint was alone in a silo. Suddenly the outline of a bear filled the only door - he was cornered. Clint reached for the .30-30 next to him and shot – the bear crumpled in a heap blocking the doorway. The gun jammed when he attempted to shoot the bear a second time but after fumbling with the mechanism he was able to shoot the bear repeatedly. Although motionless he poked the bear several times to make sure it was dead, climbed over the carcass and headed for home. (The Crazy Game, p. 4). The Finches never went off their property to hunt bears but when they encroached on the ranch they were considered fair game. Bears were attracted to leftovers from butchered beef on the ranch and Clint states that he shot bears as if they were gophers. On the ranch he was the shooter – on the ice he was the shot stopper. To complete his identity as a cowboy, Clint plays the guitar and loves Western music. Even today he is seldom seen without his ten-gallon hat. In the NHL he was and is still referred to as the Cowboy Goalie.

In addition to the Finch Ranch, Clint and Tim’s Huck Finn/Tom Sawyer playground included a homestead east of the Smoky River that Tim’s Dad had purchased in 1965. “It was a rough place, very remote, no buildings, no power or water – off the grid and wildlife could certainly be a threat.” (Band interview with Neufeld). Tim’s Dad bought a damaged 1955 Bluebird School bus for $100.00 and hauled it out to the homestead where it provided some protection from the elements while the property was being developed. From time to time Clint, Tim and his Dad spent time on the homestead and slept in the old school bus. Plywood covered the motor chamber and scars were etched on the plywood where bears had clearly tried to look through the windows of the bus. The elder Band shot more than one bear from the bus when they came within range. “We were little squirts back then but we did experience a lot.”

1955 Bluebird School bus showing scars etched on the plywood from bears. Photo courtesy of Tim Band

Lloyd Finch-submitted photo